A Fateful Shipwreck in WWII Waters

Working daily in libraries, archives, or museums often leads to unexpected discoveries—especially for those passionate about history’s hidden stories. Such was the case in late April when two knowledge-rich institutions in Tenerife received an extraordinary visitor. Charles Anthony Sangster Paterson arrived at the University of La Laguna’s Canary Islands Collection and the Canary Islands Military History and Culture Center with a remarkable donation: his father’s firsthand account of surviving the sinking of the SS Britannia during World War II.

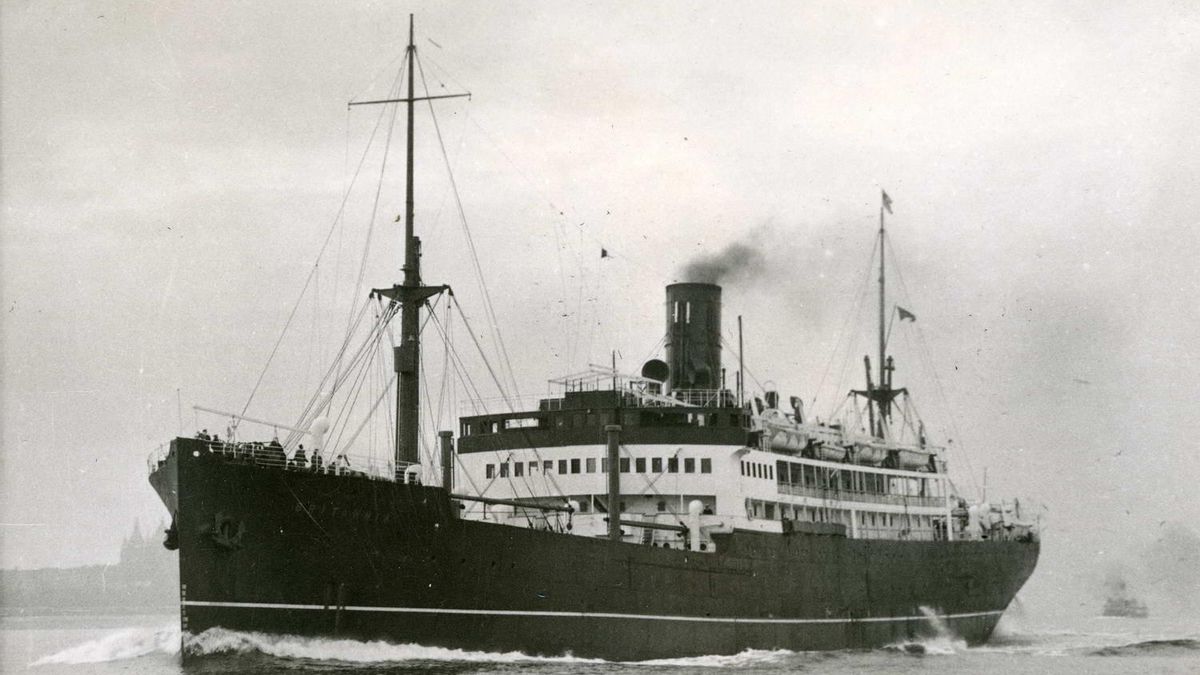

The Britannia’s Tragic End

The 8,800-ton merchant vessel Britannia, built in 1926 by Stephen & Sons in Glasgow, had departed Liverpool bound for India. Its journey ended abruptly on March 25, 1941, when the German auxiliary cruiser Thor—under Captain Otto Kähler—attacked it 750 miles west of Sierra Leone. Flying a deceptive Japanese flag, the heavily armed Thor outgunned the Britannia, which carried only a single stern cannon. Of the 484 passengers and crew, 249 perished in the sinking.

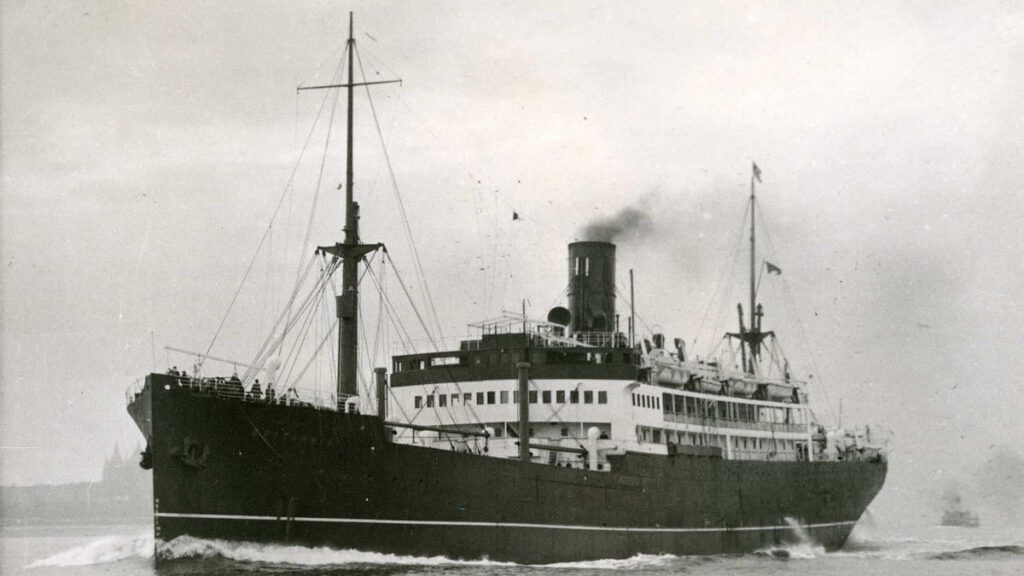

Rescue at Sea and an Unlikely Savior

Some lifeboats escaped the wreckage, including one that miraculously drifted across the Atlantic for 20 days before reaching Brazil. Among the rescued was naval lieutenant Anthony J.E.P. Sangster (1921–1992), saved after five days adrift by the Spanish merchant ship Cabo de Hornos. The vessel, en route from Buenos Aires to mainland Spain, picked up 77 survivors—thanks largely to an unidentified Spanish-American baroness aboard. She persuaded the captain to continue searching after spotting lifeboats and even donated her husband’s clothes to the ragged survivors, communicating with them in French.

Tenerife’s Wartime Dilemma

Though the Canary Islands seemed peripheral to WWII, their Atlantic position entangled them with both sides. Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy had supported Franco during Spain’s Civil War (1936–1939) and expected reciprocity. But when Hitler met Franco in October 1940 to push Spain into joining the Axis, Franco’s territorial demands and Spain’s war-torn state prevented alignment. Though technically pro-Axis, Spain’s assistance to British survivors—Germany’s sworn enemies—highlighted its precarious neutrality.

Four Months in Santa Cruz

The Cabo de Hornos docked in Santa Cruz de Tenerife on April 3, 1941, where survivors received Red Cross care before being transferred to Zerolo Clinic. Most later stayed at the English-owned Spragg and Pino de Oro hotels, near the British consulate. Their repatriation stalled for four months due to diplomatic tensions between Spain’s pro-Axis foreign minister, Ramón Serrano Suñer, and British ambassador Sir Samuel Hoare. Only as Franco distanced himself from Serrano Suñer’s German sympathies were survivors allowed to return home.

Island Hospitality in Dark Times

Sangster’s 40-page typed memoir, Lest We Forget (referencing Rudyard Kipling’s poem), details his recovery and unexpected friendships in Tenerife. Nurses Mrs. Carse and Mrs. Smith tended to him, while a local girl named Consuelo—closely chaperoned by her mother—became his language-exchange partner. “Consuelo told her parents I was a ‘professor of flattery,’” he quipped. Days began with military roll calls and prayers, followed by tennis, seaside swims, or strolls through Santa Cruz. “We were treated with great humanity by the Spanish,” Sangster wrote.

A Hidden Chapter of Wartime Canaries

This account joins others like those of survivors Jack Arkinstall and Alfred Warren in revealing Tenerife’s role as a neutral hub—reminiscent of Casablanca—where stranded travelers awaited passports under watchful eyes. Donations like Sangster Paterson’s resurrect these poignant episodes, enriching the Canary Islands’ historical tapestry and offering fresh perspectives on WWII’s global ripple effects.